Status Pages for Small DevOps Teams: Honest, Helpful Incident Updates

Most of us have a few routines for unwinding after a hard on-call week—closing the laptop, grabbing a drink, maybe a quick game on the phone. Some adults also relax with a few spins on online slot sites such as qqmamibet once the pager is quiet. Whatever you choose, remember that all gambling is for adults only and should always live inside strict limits.

In the same way you put limits around how you use a platform like qqmamibet, you need guardrails for how your team talks about uptime. A status page is where expectations, honesty, and reality collide. If it is bloated or hard to update, it turns into marketing fluff. If it is lean, truthful and easy to maintain, it becomes one of the simplest trust-building tools a small DevOps team can ship.

This guide walks through how to design an honest, helpful status page for small teams—no dedicated comms staff, just a handful of engineers rotating the pager. We will cover incident templates, uptime thresholds, and workflows that fit on-call reality instead of fantasy dashboards. Use it as a checklist the next time you ship or overhaul your status page.

Start with the smallest honest surface

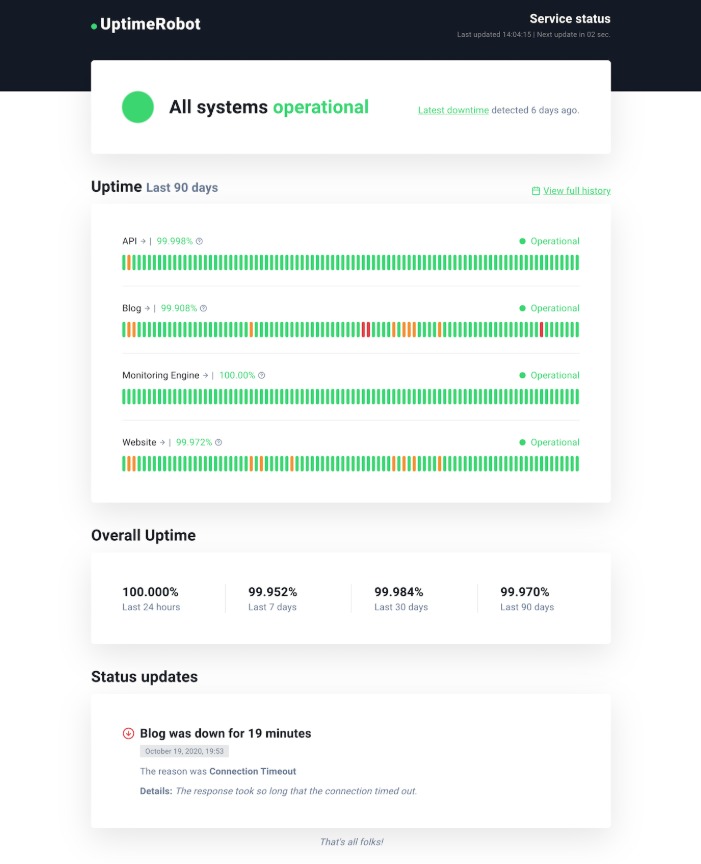

Big vendors love complex component matrices and animated tiles. Most small teams do not need that. Start with the smallest surface that still tells the truth: an overall status banner, a short incident feed, and historical uptime by product or region. Aim for “at a glance” clarity for customers and 90 seconds or less to publish an update for engineers.

A simple layout could be: top banner for current state, a list of recent incidents with timestamps, and a compact uptime graph for the last 30–90 days. Anything that does not help a customer answer “Can I trust this service today?” is probably noise for v1.

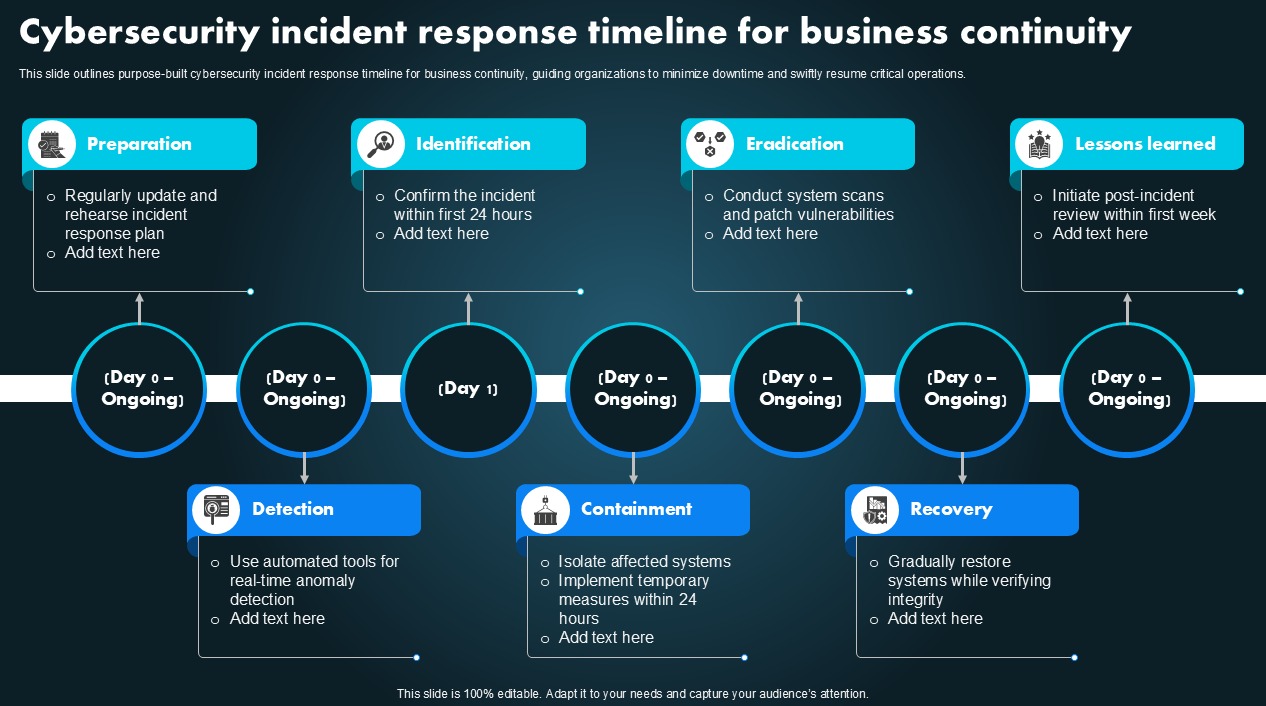

Incident templates that match reality

The fastest way to kill a status page is to make updates feel like writing a press release. Your incident template should read more like a structured log entry: short, timestamped, and written in plain language. Keep three fields mandatory for every update:

- What users see: concrete impact in user terms, not component names.

- What you are doing: investigation, mitigation, rollback, or monitoring.

- When to expect the next update: a specific time window, even if it is “within 30 minutes”.

During a live incident, your on-call should be able to paste this template into chat and fill it in without leaving the console. If your status tooling cannot be driven from the same place you coordinate the response, your updates will always lag reality.

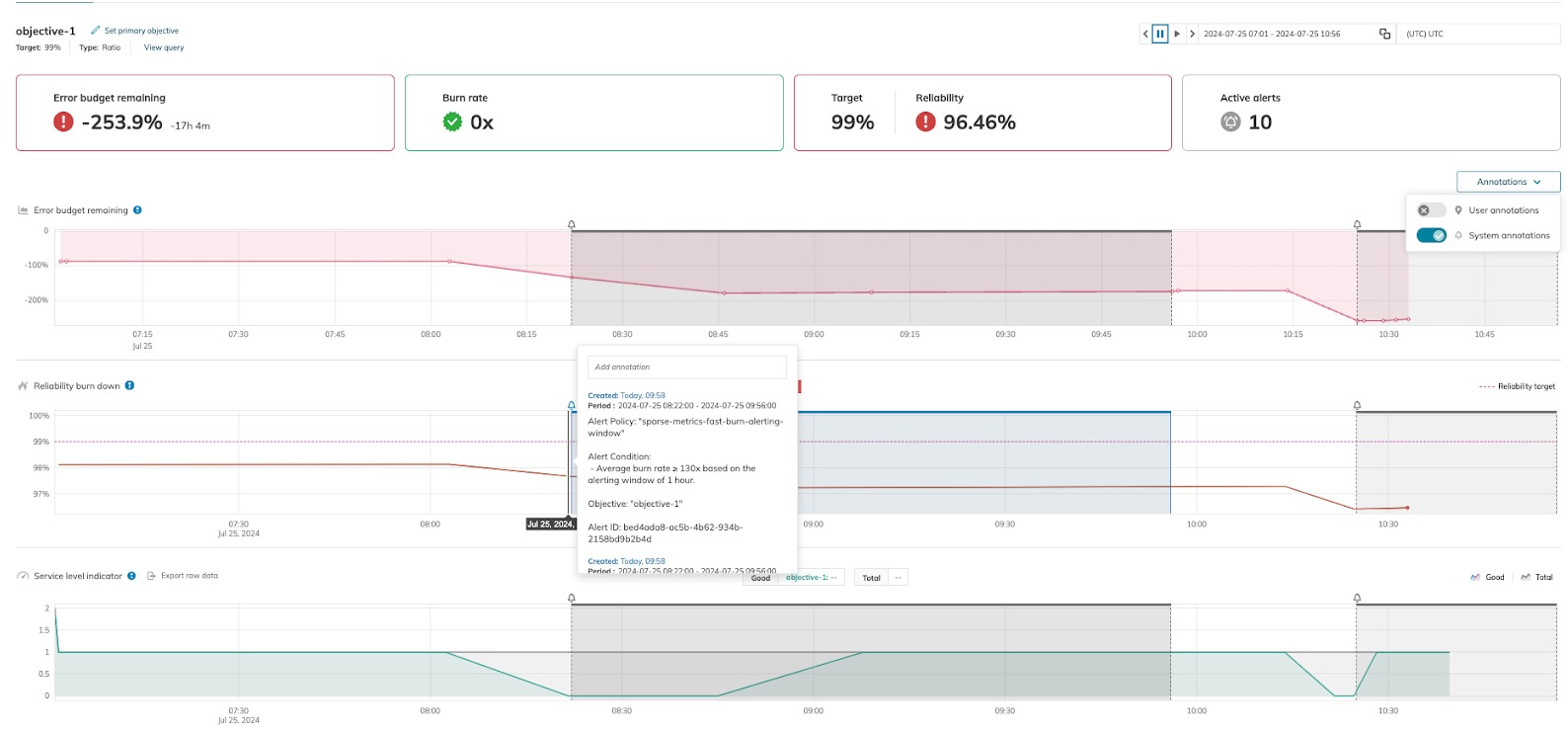

Uptime numbers that do not lie

Uptime percentages look impressive on a slide deck, but they are meaningless if the underlying rules are opaque. Small teams should define simple, public thresholds: how you measure downtime, which checks count, and how you round or aggregate data. If you hide behind “planned maintenance” for every disruption, customers will eventually stop believing the numbers.

A practical approach is to compute uptime from synthetic checks that hit the same edge endpoints your paying customers use. Maintenance windows should still count as downtime if user traffic would normally be there. Use SLO-like targets—say, 99.5% monthly availability—and share when you miss them along with what you are changing to do better.

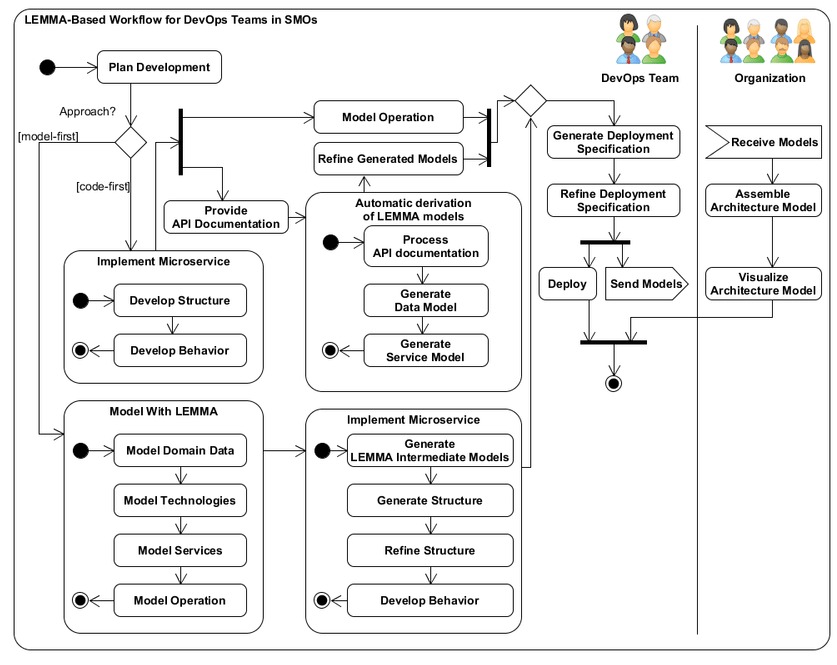

Workflows a small on-call rotation can sustain

The best status page is the one that still has fresh data months from now. Design your workflow so that updating status feels like flipping a toggle, not submitting a ticket to yourself. For most small DevOps teams, that usually means:

- One primary tool for declaring and managing incidents (chat, pager, or ticket system).

- One narrow integration point from that tool into the status page.

- A clear rule: if you page production, you update status—even if only to confirm that impact is limited.

Instead of bespoke buttons per service, give on-call engineers a couple of well-named commands or forms: “Start incident,” “Post update,” “Resolve incident.” Tie updates to your incident channel so people can see exactly what went out to customers.

Make honesty the default setting

Lean status pages are not about shaming your team; they are about reducing surprises for customers. When customers can see that you acknowledge issues quickly, share concrete impact, and follow up with clear timelines, they will trust you more than a vendor who pretends every blip was inside a maintenance window. The same discipline that keeps you from chasing losses on entertainment platforms.

Start small, write down your rules, and treat your status page as part of your product. If your team can keep one lean page up to date—during boring days and brutal nights—you will already be ahead of many bigger operations with flashier dashboards and far less truth.