Incident-Ready Logging for Small DevOps Teams (2025)

Reliable logging is the difference between guessing at 3 a.m. and fixing an outage in five minutes. For small DevOps teams, the challenge is building incident-ready logging on a single VPS without turning it into a monitoring theme park that nobody understands.

In this 2025 guide we design a lean logging stack that centralizes application and infrastructure events while staying affordable and predictable. On quiet weeks, some engineers unwind in other dashboards entirely — checking fantasy league stats or spinning a few rounds on ugwin288 for fun. That contrast is useful: your logging UI should feel the opposite of a casino, with boring, consistent patterns that make alerts trustworthy instead of random.

1. Define what “incident-ready” means

Before choosing tools, agree on what success looks like. For a small team running on one or two VPS nodes, incident-ready logging usually means:

- Single search box for most questions about errors, deploys and user impact.

- Five-minute MTTR goal for common classes of incidents (500 spikes, CPU starvation, cache failures).

- Readable alerts that point to log queries or saved views, not just CPU percentages.

- Storage tuned by retention so hot logs are fast and old logs are cheap.

Write these constraints into a short logging charter. It becomes the lens through which you decide which features to enable now, later or never.

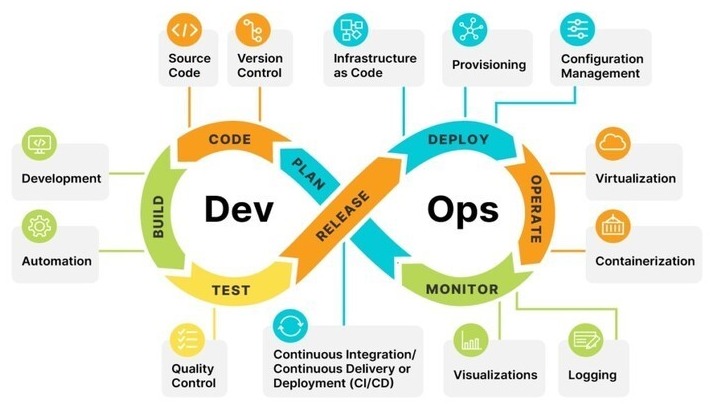

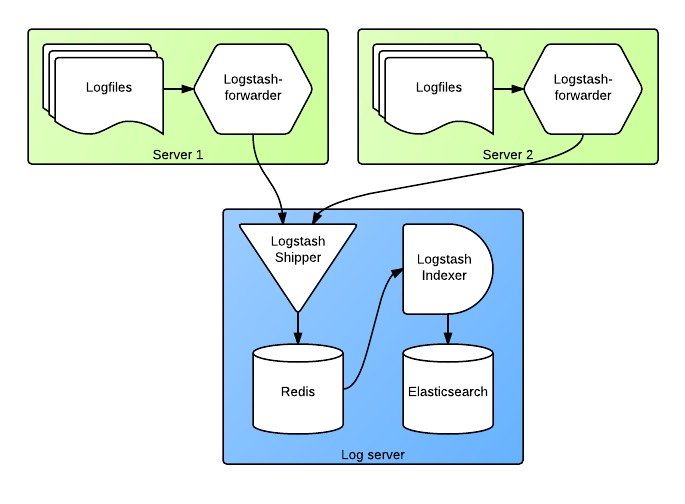

2. Core components on a single VPS

A minimal incident-ready stack on one host can be built from four pieces: log shippers, a central receiver, storage + index, and a thin UI. There is no rule that says you must run a full ELK stack; for many teams a lighter setup built around Vector, Loki or OpenSearch is enough.

Start with Linux service logs and application logs. Run a local agent on each node that tails files and systemd journals, adds metadata (service name, environment, instance) and forwards over TLS to the logging VPS. Keep formats boring: JSON for structured logs, plain text otherwise. The goal is to make logs trivial to parse and filter in the heat of an incident.

3. Schemas, fields and search patterns

Incident response lives and dies on how easily the on-call can answer “what changed?” and “who is affected?”. Define a tiny, consistent schema up front:

env– production, staging or sandbox.service– human-readable service name.request_id– trace-style correlation ID.user_idortenant– safely anonymized where required.level– debug, info, warn, error.

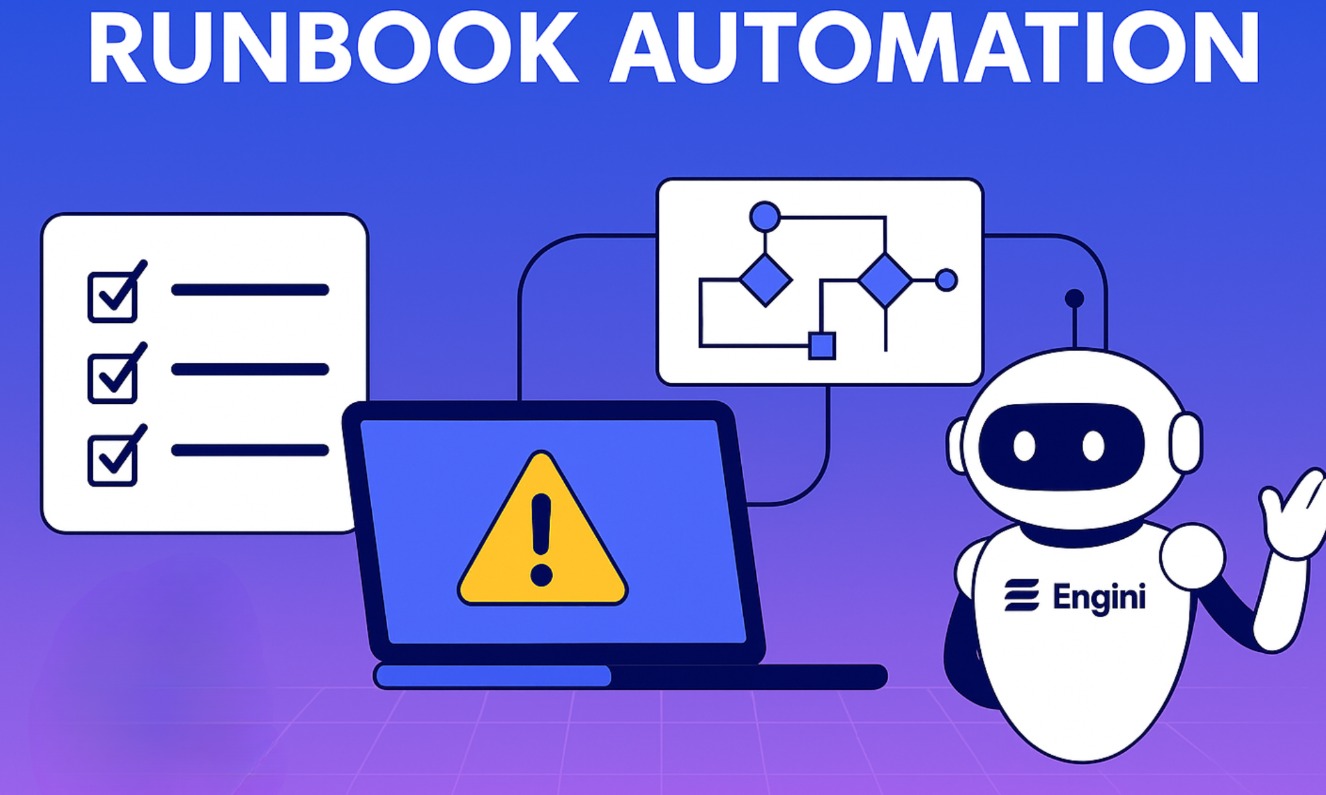

Then, build a library of saved searches around that schema: “all 5xx by service in the last 15 minutes”, “deploy logs for service X”, “auth failures by tenant”. These saved queries become links inside alerts, runbooks and incident channels.

4. Alert design that respects on-call

Alert fatigue kills small teams faster than outages. Instead of wiring every threshold directly to pager notifications, separate signals into three tiers: dashboards, chat alerts and paging alerts. Most log patterns should land in the first two tiers, used for triage and context rather than waking people up.

For paging alerts, tie them to symptoms a user would notice: error rate, latency and availability. Each alert should contain:

- A short human sentence describing the impact.

- A direct link to a saved log query.

- Hints from previous incidents (runbook or ticket IDs).

If your logging stack cannot produce stable, low-noise alerts, trim inputs and simplify fields until it can. Reliability beats cleverness.

5. Runbooks, drills and log hygiene

Logging is only incident-ready if people know how to use it under stress. For the top five alert types, create short runbooks that start with a log search, then branch into common fixes. Keep them close to the tools: in a shared Git repo, wiki or status page linked from alerts.

Once a quarter, schedule a one-hour drill. Trigger a synthetic error burst in staging, have someone on-call follow the alerts, runbook and log searches, and then adjust the stack based on what slowed them down. This tiny investment makes real incidents calmer and shorter.

6. Storage, retention and exit ramps

Finally, resist the temptation to ingest everything forever. Define three retention classes: hot logs (hours to days, fast SSD), warm logs (weeks, slower storage) and cold archives (months, object storage or compressed files). Map services into those classes based on how often they feature in incidents.

Choose tools and wiring that you can migrate away from later: standard syslog or HTTP ingestion, open formats, export jobs that can write to S3-compatible buckets. If you ever outgrow a single VPS, being able to replay logs into a larger cluster or a managed service without rewriting your applications is invaluable.

Key idea: incident-ready logging is not about having every feature; it is about having the right small set of features, tuned to how your team actually debugs production. With a lean stack, clear fields and disciplined alerts, you can centralize logs on one VPS today and still feel ready when the phone rings at 3 a.m.